The fundamental problem of causal analysis

25 Aug 2016

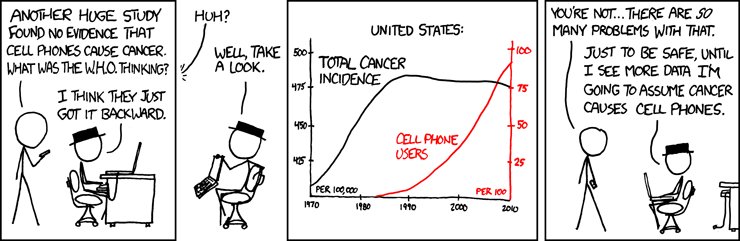

“Correlation does not imply causation” is one of those principles every person that works with data should know. It is one of the first concepts taught in any introduction to statistics class. There is a good reason for this, as most of the work of a data scientist, or a statistician, does actually revolve around questions of causation:

- Did customers buy into product X or service Y because of last weeks email campaign, or would they have converted regardless of whether we did or did not run the campaign?

- Was there any effect of in-store promotion Z on the spending behavior of customers four weeks after the promotion?

- Did people with disease X got better because they took treatment Y, or would they have gotten better anyways?

Being able to distinguish between spurious correlations, and true causal effects, means a data scientist can truly add value to the company.

This is where traditional statistics, like experimental design, comes into play. Although it is perhaps not commonly associated with the field of data science, more and more data scientists are using principles from experimental design. Data scientists at Twitter use these principles to correct for hidden bias in their A/B tests, engineers from Google have developed a whole R package1 around causal analysis, and at Tesco we use these principles to attribute changes in customer spending behavior to promotions customers participated in.

In this post we will have a look at some of the frequently used methods in causal analysis. First, we will go through a little bit of theory, and talk about why we need causal analysis in the first place (the fundamental problem of causal analysis). I will then introduce you to propensity score matching methods, which are one way of dealing with observational data sets. We will wrap up with a discussion about other methods, and I have also put up an IPython notebook that walks you through an example data set.

Preliminaries

Before we delve deeper into some of the theory, let’s define some standard terminology. We will consider a binary treatment variable \(T \in \{0, 1\}\), where \(T = 1\) denotes that one received the treatment and \(T = 0\) denotes otherwise. \(T\) could be any phenomenon we want to measure the causal effect of. It could be a new drug for a disease, a new kind of supplement, a new website design, or a commercial TV or email campaign your company ran.

We also define a variable \(Y_T\), that denotes the response for each value of the treatment \(T\). For example, in case \(T\) was a promotion we ran in-store, \(Y_1\) would be the response (which could be something like total spend in the weeks after the promotion) if a customer bought a product that was part of the promotion, and \(Y_0\) would be the response if a customer did not buy into the promotion. Finally, we introduce another variable \(Y\), that denotes the actual observed value of the response.

For convenience, I am suppressing any subscripts \(i\) to identify individual observations in the above.

The fundamental problem of causal analysis

Usually, we are interested in either the average treatment effect (ATE)

\[ATE = \mathbb{E}\left[\delta\right] = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_1 - Y_0\right],\]which is the average (over the whole population) of the individual level causal effects \(\delta\), or we are interested in the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT)

\[ATT = \mathbb{E}\left[\delta \,\vert\, T = 1\right] = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_1 - Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right],\]which is the average of the individual level causal effects for the observations that got treated, and is useful to explicitly measure the effect on those observations for which the treatment was intended.

In case of our promotion example, the ATE would the average difference in customer spend between customers that did and customers that did not participate in the promotion. The ATT would be the average effect only for customers that participated.

However, we will run into a problem when we try to directly compute these quantities. For a customer that participated in the promotion, we can never simultaneously measure the response in case they did participate, and the response in case they did not participate. We never observe both \(Y_1\) and \(Y_0\) for the same individual. The fact that we are missing either \(Y_1\), or \(Y_0\), for every observation is sometimes referred to as the fundamental problem of causal analysis.

Randomized trials as the gold standard

How can we solve this problem? Let’s focus on estimating the ATT for now. We would like to compute this effect directly, but in reality we only have the estimator

\[\begin{align} \hat{ATT} &= \mathbb{E}\left[Y_1 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] - \mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 0\right] \\ &= (\mathbb{E}\left[Y_1 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] - \mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right]) + (\mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] - \mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 0\right]) \\ &= ATT + bias. \end{align}\]In the second step we used a small trick where we effectively added zero to the equation, because \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] - \mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] = 0\). The remaining bias is the difference between the treated and control observations in absence of treatment, and this bias is called selection bias.

The ATT measures causation, but the above estimator only measures association.

In general, these two are not equal, and this is where the phrase “correlation does not imply causation” comes from. It is also referred to as the identification problem: we can’t easily separate causation from association.

To tackle this problem, we will need to make some assumptions, as assumption-free causal analysis is impossible. If we want the estimator \(\hat{ATT}\) to be equal to the ATT, we need the selection bias to be zero. Under the assumption

\[\mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 1\right] = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_0 \,\vert\, T = 0\right],\]we get that the selection bias disappears and that the estimator \(\hat{ATT}\) is a consistent and unbiased estimator of the ATT, which means that association actually equals causation in this case.

In words, this assumption means that the outcomes from observations in the treatment and control groups would not differ in the absence of treatment. On average, observations in the treatment group and observations in the control group are similar to each other, with respect to the potential outcomes.

This can be achieved by using a random sampling design, where you randomly assign treatment to observations in your population, and this is why a randomized experiment is sometimes called the gold standard in experimental design.

Observational studies

In reality, we mostly deal with data that does not come from a carefully set up randomized experiment. We deal with observational studies, where treatment assignment is typically not random, and influenced by external factors. In case of the promotion example, we have no influence in who does or does not participate in the promotion and participation is typically driven by external factors, like how much money people can spend on their groceries shopping.

How do we still come up with unbiased estimates of the ATE and ATT? One popular approach to this problem is to use matching methods.

Matching methods

Matching methods try to structure the observational data in such a way, that we could think of the data as if it was generated by a random sampling design. To understand the idea behind these methods, let’s have a look at the promotion example.

Imagine that there is a customer called Bob, and that Bob has an identical twin-brother called Bill. Bob and Bill have the same shopping habits, they like the same products, they have the same amount of money to spent, and they prefer to do one big weekly shop instead of shopping everyday at their grocery store.

Their grocery store now launches a big promotion to promote their new line of products, and Bob decides to try some of the new products, but Bill decides not to buy any. Because Bob and Bill are so similar, any difference in their spending behaviour after the promotion is precisely the effect of the promotion.

This is how matching methods try to measure the causal effect:

- For every participating customer, we find a matching twin customer.

- The promotion effect is then the average difference between each pair of customers.

Propensity score matching

Usually, we find a matching observation by looking at a set of covariates \(X\) that are known before the treatment is applied. In general, it is very hard to find an exact match for every observation, especially if \(X\) is of high dimensionality.

Propensity score matching is a simplification of the matching procedure. Instead of matching directly on the covariates \(X\), we match on the individual propensity scores \(p\). The propensity score is the likelihood (or probability) that an observation receives treatment (a customer participates in the promotion).

Propensity score matching works as follows:

- Estimate a probabilistic model that predicts the likelihood of receiving treatment based on some set of pre-treatment covariates \(X\). We can use any probabilistic model for this, but most commonly generalized linear models (GLMs) or generalized additive models (GAMs) are used.

- For every observation in the treatment group, find a similar observation in the control group based on their propensity score \(p\).

- Estimate the treatment effect by comparing the treatment group with the group of matched control observations.

In the second step of the above procedure, we need to find a matching observation in the control group for each observation in the treatment group. There are many different approaches available for matching observations with each other. The most common matching methods based on the propensity score are

- \(k\)-nearest neighbour matching, where we find the \(k\) nearest control observations;

- radius matching, where we take all the control observations that fall within a pre-defined radius \(R\) of the treatment observation;

- stratification matching, where we pool all (both control and treatment) observations together in disjunct strata based on the propensity score. The treatment effect is then estimated as a weighted average of the treatment effect in the different strata.

In \(k\)-nearest neighbour matching and radius matching you also have the choice to discard a control observation from the set of potential candidates, once you have matched the control to a test observation. This is referred to as matching with (when you keep the control) or without replacement (when you discard the control).

In general, matching with replacement is preferred because in matching without replacement the final matching becomes dependent on the way the data was initially sorted. Hence, your matching may be biased by this sorting.

Turning theory into practice

Now that we have processed the necessary theory, it is finally time to get our hands dirty and see how these methods work in practice! I have put up an IPython notebook that works through a well known academic data-set, called the LaLonde2 data set.

Here, we look at the effect of a job training program (the treatment) on real earnings a number of years after the program (the response). The original data set is unbalanced in the pre-treatment covariates, and hence any direct analysis of the treatment effect will not be accurate. The notebook shows how you can build a propensity score matching method in Python, and gives some practical advice on post-matching validation checks.

If you prefer to work in R, you should definitely check out the excellent MatchIt3 package. To my knowledge, there is no robust package for (propensity score) matching methods in Python available yet.

Final words and further reading

Propensity score matching methods can be a good solution when we are analyzing data from an observational study, but these methods by no means guarantee proper balancing in the processed sample. We always have to check how well the sample is balanced after the matching, and usually we should iterate, by varying the propensity model formulation and the matching method, until we are happy with the resulting balance. Even then, there may still be selection bias present in your data.

What can you do in this case? There exists another class of matching methods, called monotonic imbalance bounding (MIB) methods. MIB methods allow you to choose a maximum imbalance, or they will reduce the imbalance in one covariate without changing the imbalance in others. An example of a MIB method is the so-called coarsened exact matching4 (CEM) algorithm, on which I may dedicate a future blog post. CEM is supported in the MatchIt R package, but there is no open source Python implementation available.

Another common approach in analyzing observational studies is to apply a Heckman correction5 to your data. This is a two step procedure, where the first step again estimates a propensity model, and the second step consists of including a transformation of the propensity scores into a regression model that estimates the treatment effect.

In the end these are still approximate methods however, and you may still end up with a data set you can’t properly analyze. Even if you have perfect balance in the pre-treatment covariates you measured, you may still have a flawed design because of a confounding variable, of which you did not know it existed. If you have the choice, you should always prefer proper experimental design above post-experiment data processing techniques.

References

-

Brodersen, K. H., Gallusser, F., Koehler, J., Remy, N., & Scott, S. L. 2015. Inferring causal impact using Bayesian structural time-series models. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 9(1), 247-274. https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/41854.pdf ↩

-

Dehejia, Rajeev and Sadek Wahba. 1999. Causal Effects in Non-Experimental Studies: Re-Evaluating the Evaluation of Training Programs, Journal of the American Statistical Association 94 (448): 1053-1062. https://www.nber.org/~rdehejia/papers/dehejia_wahba_jasa.pdf ↩

-

Daniel E Ho, Kosuke Imai, Gary King, and Elizabeth A Stuart. 2011. MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference, Journal of Statistical Software, 8, 42. https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v042i08/v42i08.pdf ↩

-

King, G. 2008. Matching for Causal Inference Without Balance Checking, Applied Statistics, 10, 1. https://gking.harvard.edu/files/gking/files/political_analysis-2011-iacus-pan_mpr013.pdf ↩

-

Heckman, J. 2013. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Applied Econometrics, 31(3), 129-137. https://faculty.smu.edu/millimet/classes/eco7321/papers/heckman02.pdf ↩